Behaviour Change Using Gamification

In previous chapters, we talked about different theories of motivation from the Hierarchy of Needs to Equity Theory. And there’s more psychology to come. However, now, we’ll focus on the changes we want to create through gamification. It is psychology, after all, that makes gamification work.

In this section, we’ll cover some theories around feedback loops, what makes rewards effective and how all this combines into positive behaviour change using gamification.

Chapters

You are in Chapter 4 of the Beginner’s Gamification Guide.

Gamification can actually make the world a better place. Yep, we mean that. Because gamification is a tool for changing behaviours, it can be a powerful force for good. From motivating people to make healthy food choices or eliminating waste, gamification and its behaviour changes can help create a better society. (But it can also sell a whole lot of consumer goods, generate inquiries and solve help tickets.) Pretty strong stuff. But how can one thing be so omnipresent and multi-purpose? When behaviours are just actions & mannerisms made by entities within an environment, you see that it’s a pretty universal trait. But let’s explore behaviourism a bit more.

What is behaviourism?

First off, behaviourism is a theory. The principle states that every behaviour we have is the result of conditioning. It also talks about how we are conditioned by our environment. That makes our behaviour easy to study because our actions are largely ruled by an environmental stimulus. In behaviourism, you can overlook emotions, thoughts and mood when you’re studying behaviour and focus just on what you can see. Rigorous followers of behaviourism argue that anyone can learn anything (except with regard to physical limits) through conditioning alone.

Putting in more than you get out? The result is anger. Feeling overpaid? You’ll experience guilt. While Adams uses hourly or salary wages as the main indicator of this input and output calculation, it’s likely to apply to other soft benefits as well like respect, appreciation and togetherness. Adams was one of the early psychologists to note the value of recognition in the workplace as a powerful tool for improving their own self-assessment of equity. Impressively, it’s also included in his process theories of motivation as a driver.

How is behaviourism related to gamification?

Behaviourism is a bit one-dimensional, critics would say. It states all behaviours are learned and nothing is innate or inherent. And while there are some elements of behaviourism in gamification, it’s not a “push button, get some cake” environment. The Skinner box is a simplification of what gamification is and so is behaviourism. To create behaviour change, gamification goes deeper to look at the moods, feelings, thoughts and free will of the individual to get a fundamental understanding of their personality drivers and learning ability. Gamification believes we need to account for differences in people, products, approaches and outcomes. But behaviourism is a useful reminder that conditioning based on consequences does work. Reward systems, punishments and reward frequency are all influencing factors on behaviour. And we’ll talk about most of those later on.

Behaviour Change in 6 Stages

If you’ve ever tried to keep a new year’s resolution, you know that behaviour change is hard. You need to commit time, manage your emotions and expend a great deal of effort to create a long-lasting habit.

And what works for one person might not work for another. Our motivators are all a little different after all. You might need to go through many changes, trial and error, new approaches and setbacks to reach your ideal behaviour change state. What’s important is finding ways to stay motivated during this process. Gamification can help you do this by creating fun drivers that keep you pushing forward when you want to learn something new or reach a goal.

Since change isn’t easy, we’ll explain the different states you’ll go through. This will help you to understand better how to meet your goals.

Change Factors

It seems intuitive, but it’s worth noting that there are several factors which influence the ability to change. First, do they want to change? That’s the very first step. If they don’t want to, they won’t. Are the tools, resources and knowledge at their disposal? Second, what’s stopping them? Are there barriers? If people have something competing for your time and attention; they might not be able to maintain their commitments. Lastly, when might one fall back into old behaviour? What could trigger a relapse for them? When people keep these factors in mind, every behaviour change programme -gamified or not- has a better chance of success.

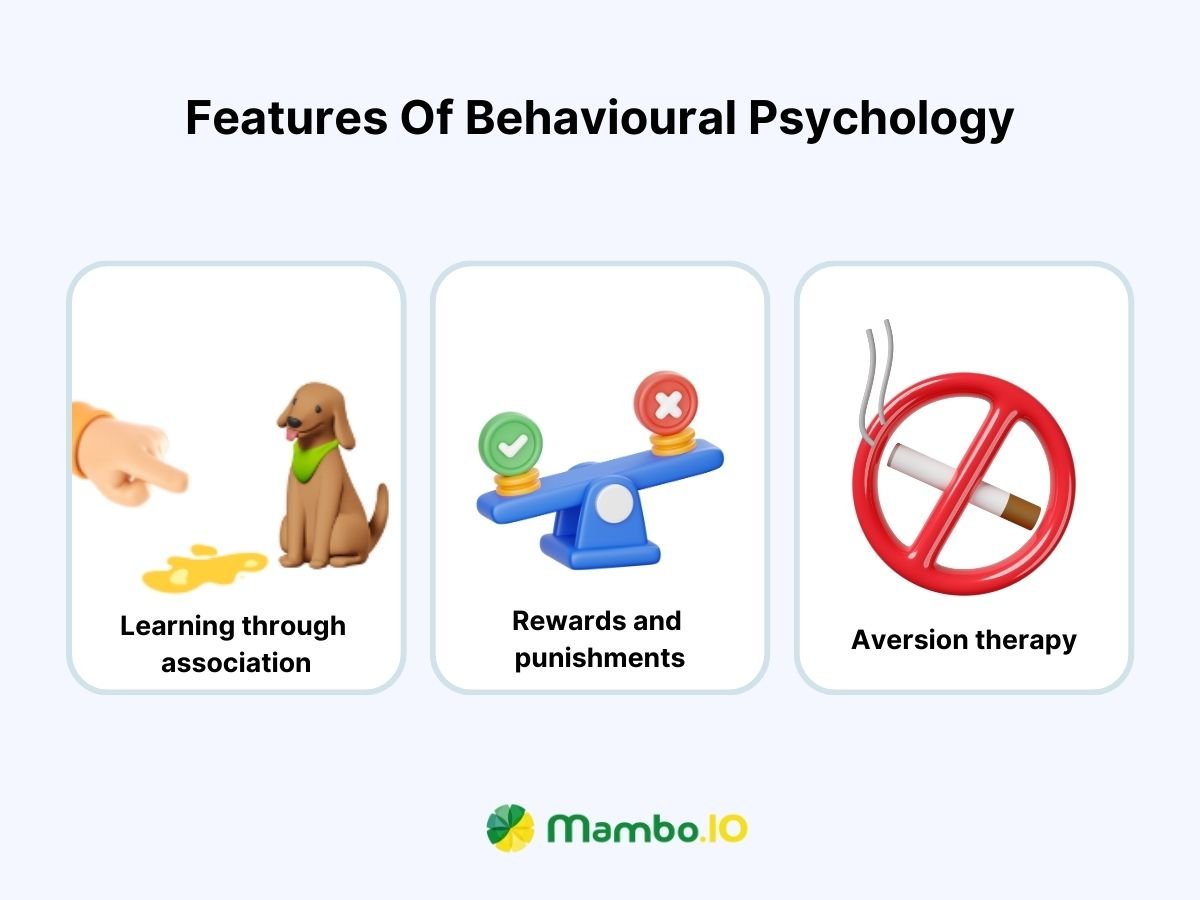

The different stages of change

The Transtheoretical Model from the 70s is one of the best-known approaches to long-term behaviour change. Created by James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente as a model to encourage smoking cessation, it’s been shown effective in the general understanding of behaviour change.

Looking at the model, you get real behaviour change over time and you must factor in relapses as natural growth. While you might be unwilling at first, you’ll get more motivation as you see incremental successes. Each of these small wins will help you (eventually) reach your behaviour change goal over time.

The Precontemplation Stage

What it looks like

- Denying there’s an issue

- Not understanding the problem

What to do

- Rethink this behaviour

- Analyse your actions and beliefs

- Document the risks if no change is made

During precontemplation people don’t really want to change. They’re in denial that their behaviour is causing a problem. Maybe they don’t see the consequences of their actions or don’t understand damage is happening. In this stage, they think they don’t have any control over things. And people might resign themselves to being this way forever. But, people can take charge. Think about what could happen that would tell someone this behaviour is a problem. Have they tried to change in the past? This will get your brain headed in the right direction for stage 2.

The Contemplation Stage

What it looks like

- Contradictory ideas

- Differing emotions

What to do

- Make a behaviour change pro/con list

- Affirm you are ready and can change

- Note any risks or barriers to behaviour change

At stage 2, people start thinking a change might be for the better. But they are seeing the struggle ahead. They know that it might be hard and they’ll need to do things differently. This stage can take a while to get through as people become internally conflicted. Some people never move past contemplation. This is especially if they’re framing it from a negative space of what they’re losing. Instead, look at what one will gain. Some helpful thinking points are around why they’re thinking of behaviour change and what’s stopping them. People think about how they could make change easier for themselves to begin the journey to stage 3.

The Preparation Stage

What it looks like

- Trying little changes

- Learning about the change

What to do

- Make a list of goals and motivating statements

- Create your plan of action

Here’s where they actually start making little changes to snowball into the big behaviour change they want to see. If people are looking to shed pounds, maybe they give up sugar. Or maybe they want to quit booze, so choose to only drink every other weekend. In the preparation stage, people might seek professional support or buy supplies to help them. In order to set up for success, people should seek out information about different methods, write down motivators and their goals and find other people to support & encourage them.

The Action Stage

What it looks like

- Taking action towards a goal

What to do

- Rewarding each success

- Seek out social support

This is the stage where real action is taken. Here, people use gamification or other methods to reach their goals. When people get social recognition and intrinsic or extrinsic rewards, these little wins reinforce their steps towards a behaviour change. (Gamification does all of these.) But people shouldn’t jump right into the action. Without the other steps, people may find these good behaviours are abandoned because they’ve not done the preparation. Remember that rewarding your audience, employees and customers is important. At every milestone, give them a little recognition for what they have accomplished. Look for those social bonds that can reinforce their actions and think about how they can keep this positive momentum going to bring on the next stage.

The Maintenance Stage

What it looks like

- Maintaining new behaviour

- Saying no to temptation

What to do

- Practise addressing temptation

- Reward often

In this part of the States of Change model, they are training to keep up with their new, ideal behaviour changes. People might be tempted to go back to their old ways here and that’s okay. If they create strategies to prevent temptation, quickly recover from setbacks and the gamification is rewarding them for the behaviour change; they are more likely to remain in this stage for longer. Gamification can be really helpful in this step. Through game elements and mechanics, they can track their progress, maintain new habits and reach levels of behaviour change while getting rewarded along the way. If they do move on to step 6 (relapse), it’s normal and gamification can make getting back on track more fun for them.

The Relapse Stage

What it looks like

- Annoyance and frustration

- A sense of failure

What to do

- Note why relapse happens

- Document barriers to success

- Refresh the commitment

With a video game, players sometimes fail and see a ‘you lose’ message. That’s a normal part of the progression. Sometimes people trip up. As with any behaviour change, they’ll often relapse. But don’t let these setbacks and feelings of disappointment taint their progress. When using gamification to help them overcome relapses, they’ll have a record of progress to look back on and appreciate. This can help them get their motivation back and think critically about what caused them to falter. As with any game, failure is a natural part of the process and they can try as many times as they need to until they reach that ‘win’ state. Just take the focus back to starting again with preparation, action, maintenance and so on.

You probably don’t even notice them. However, feedback loops are at the core of all behaviour change. When you do anything, you’re looking at the outcome. The more you know about the consequences, the more you can maintain or adjust your behaviour in the future for the best results. (Gamification helps you get this feedback in near real-time. The faster you are alerted, the more effective this data is at reinforcing or balancing your behaviour.) Balancing loops are used as fuel for behaviour change when we have bad habits or need new habits. Whereas, reinforcing loops double down on our existing habits. We’ll describe both types of loops and how they relate to behaviour change in more detail below.

Feedback loops provide people with information about their actions in real-time, then give them a chance to change those actions, pushing them toward better behaviours.

—Thomas Goetz

Balancing Feedback Loops or Negative Feedback Loops

Balancing loops are a stabilising force. If we need to kick a bad habit or make a new good one, negative feedback loops are the ideal mechanism. For example, if you see a digital speed sign that tells you to SLOW DOWN, you’re likely to do so. In fact, these have been shown to reduce speeds by as much as 10%. Do you see how this is a feedback loop? You’re shown something about your current actions that you don’t like and so you use that information for behaviour change. It’s just like how a thermostat regulates the temperature of your room. Measure/adjust. Measure/maintain. Gamification helps us do this with our habits in a fun and creative way. It offers real-time feedback on how we’re doing and lets us self-regulate in response.

Here are some examples of how balancing feedback loops are used in gamification to create good habits and stop bad ones.

- Not paying attention to new product information? Gamification can put a flashing timer on your screen giving you an expiring badge if you complete it within the first 24 hours of launch. This creates a feedback loop that reminds you to read the material in a timely fashion.

- Need to make more sales? Use gamification progress bars to apply the paper clip strategy in a much more modern way. As you make your sales calls, the app tracks your progress and rewards you when you hit your daily and weekly goals.

Balancing feedback loops are used in gamification (and outside of it) to remind you to do productive actions and reduce the occurrence of unhelpful behaviours.

Reinforcing Feedback Loops or Positive Feedback Loops

Reinforcing feedback loops are like amplifiers. They boost your behaviour change to help you increase or maintain good behaviours. For example, let’s say you have a telematics device in your car. After every trip, it gives you a score for your driving based on speed, braking and time of day. You know if you get a good score, your insurance premiums will go down. So, now, every time you drive, it’s a game to keep your score in the green. When you do, you get the savings that come with the good behaviour of driving safely. This device essentially gamifies driving in a slow and steady manner. That’s good for other road users and great for your wallet.

But reinforcing feedback loops can increase bad behaviours too. Let’s take the office gossip that’s spreading a nasty untruth that you’re leaving work 15 minutes early every day. As the rumour gets around and more people hear and share it; it spreads like cancer. This is an effective example of a bad reinforcing feedback loop. But, did you know you can create your own feedback loops and harness them for good? We’ll explain.

How to Build Your Own Feedback Loops

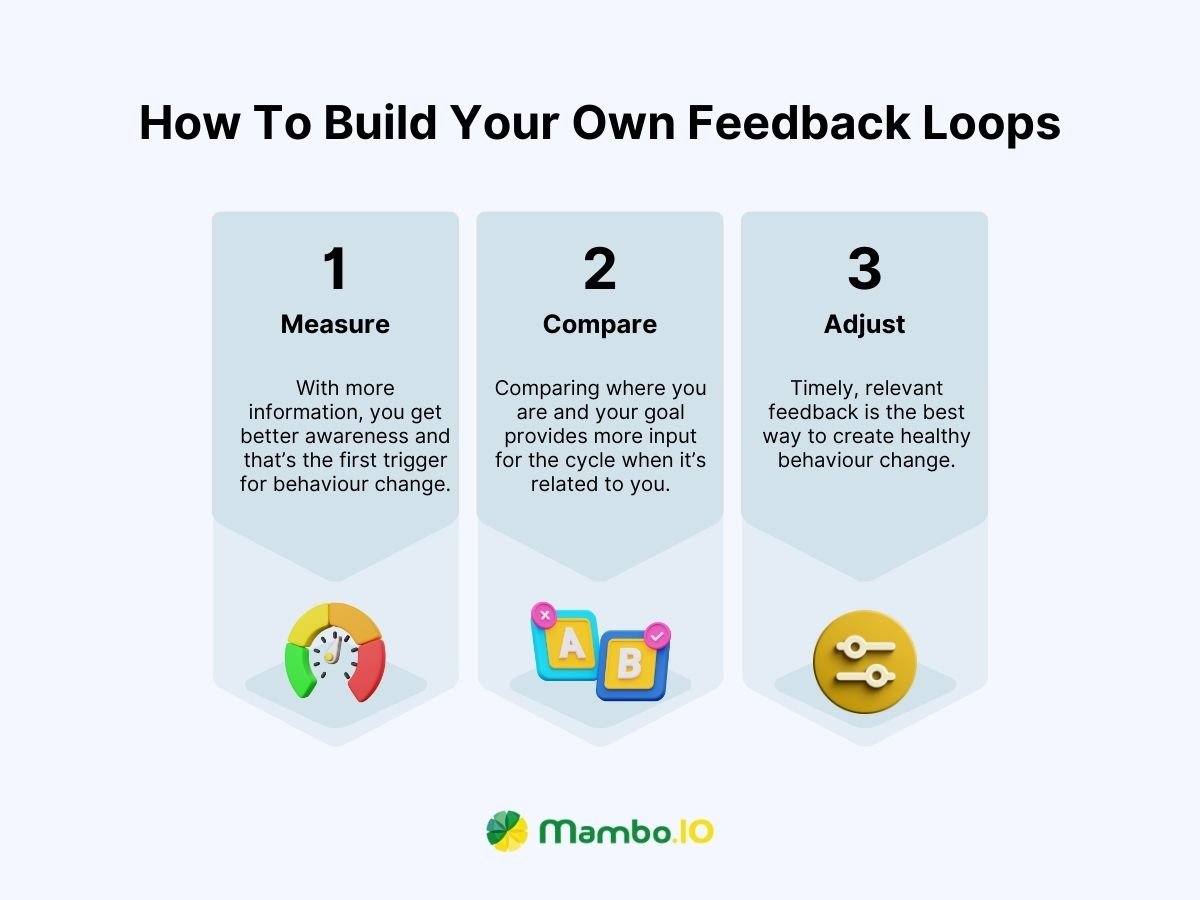

Here’s a three-step approach to creating helpful feedback loops in your own life:

- Measure – You need data. Since the outcome of one cycle is the beginning of the next cycle, then accurate measurements lead to better results. With more information, you get better awareness and that’s the first trigger for behaviour change.

- Compare – Then, once you have data, you need to compare it against your actions and find the relevance. Comparing where you are and your goal provides more input for the cycle when it’s related to you.

- Adjust – Once you measure and compare, then you need to adjust to close the loop. The faster you make the change relative to the outcome, the tighter your loop will be. Timely, relevant feedback is the best way to create healthy behaviour change. (And gamification is great for this!)

When Feedback Loops Fail

Creating a persistent loop to stop bad habits and build positive behaviour change is a great approach. Take patients who forget to take their pills. When Vitality launched GlowCap, they looked to create a feedback loop to solve this problem. The cap of the pills was set to the patient’s medication schedule and would glow in increasing insistence to remind them to take their pills. If they still didn’t open the bottle, they would get reminders via text/phone. But sometimes these interventions don’t work. Here’s why:

- No automatic measurement.

- Irrelevant comparisons.

- Slow feedback.

The GlowCap was successful because it avoided all these pitfalls. The measurement is in real-time and to your specific prescription (relevance). Then, it’s comparing the current time with your medication time to see if you need a reminder (measurement). Last, it tells you immediately and with increasing intensity to do the behaviour (feedback).

Rapid Feedback Leads to Rapid Change

If you don’t know where you stand, how can you know what behaviour change you need? Want to lose weight? That’s a common goal. But are you tracking your calories? If not, your lack of measurement means you’re not even taking the first step to creating a successful feedback loop.

But you can make this an intentional process instead of just letting feedback loops form without a helping hand. Remember, behaviour change from feedback loops can be both good and bad. You wouldn’t want to pick up a bunch of bad habits because you’re not examining and creating the feedback loops you want, right? Be the architect of your feedback loops instead of a casual bystander to create the behaviour changes you need to be your best self.

Next, we’ll talk about the social impacts of behaviour change. There are two primary theories: Social Comparison Theory and Personal Investment Theory. They both look to explain games. Social Comparison is where you measure yourself (ability, attitude, beliefs) with others. However, Personal Investment postulates that the amount you’ll put in depends on what’s in it for you, what you think about yourself and what other choices you have.

The Social Comparison Theory

In 1954, Festinger proposed the Social Comparison Theory. It argues that you know more about yourself by comparing yourself to others. When we evaluate our skills, thoughts and reactions to other people, we can exercise our ‘unidirectional drive upward’ to improve ourselves. In short, you want to make sure your position is better than those around you. Of course, what you’re comparing and your degree of competitiveness will vary. You may compare yourself to those like you or someone dissimilar. When you do a downward comparison, you’re looking at people less well-off than you. And an upward comparison is the inverse.

In 1989, Wood would argue that Social Comparison is based on a self-improvement motivation. Looking at aspirational figures shows you what’s possible with behaviour change. Inversely, looking at those in unfortunate circumstances is a cautionary tale. In gamification, you’re getting this feedback in comparison with others in the form of high scores or leaderboards. These might compare you against universal best performance or lump you into groups based on job role, age, ability or some other determining factor. This comparison fuels competition – this challenge encourages us to try harder and get better. Like a car racing game, you’re always looking at where you are in relation to others. You’re making quick calculations. Am I winning? Am I losing? Overall, you’re trying to judge where you are in the pack. This simultaneous upward and downward social comparison were noted by Gilbert et al. in 1995. That means your self-belief ( and self-esteem) is impacted in real-time.

Personal Investment Theory (PIT)

Personal Investment Theory (PIT), on the other hand, mixes achievement motivation with social influences. It takes a holistic view of the meaning we derive from beliefs, feelings, goals, perceptions and more. This look seeks to understand why we act and what drives any behaviour change. This social cognitive theory assumes that our persistence, choice and variation in activity come from our cultural and social beliefs. These turn into our thoughts, values and perceptions around the self and our circumstances.

The three basic components of meaning deemed critical by Personal Investment Theory are:

- What we think about ourselves and who we are.

- What our goals are for how we’ll act in any given situation, including what success looks like.

What the behavioural alternatives are (based on our culture).

Rewards matter in behaviour change. Maybe that’s why they’re such a big part of gamification. It’s largely because we’re motivated by rewards (internal and external). When choosing an action, rewards help us find the best option. Maybe we want to have a tasty dinner. A Michelin Star may signal that a restaurant further afield is worth the journey for the reward of culinary masterpieces.

When it comes to behaviour change, we’re evaluating these rewards within the culture and society that we live in. Praise, feedback and approval are all valid rewards (sometimes even more motivating than a physical prize). This is why gamification seeks to incorporate a range of rewards: social, physical, extrinsic and intrinsic. Plus, any good motivator of behaviour change will look to account for personal preferences. Understanding where we see value will impact our reward-seeking prioritisation. When we get a reward we really value, we see dopamine released which gives us chemically-induced motivation to keep going.

What rewards can we use in Gamification?

Because our actions and behaviour change are based on outside reinforcement and internal beliefs, we need to combine our motivators. Gamification sees us use external rewards like prizes AND internal drivers like autonomy, a sense of belonging and skill mastery to encourage us to act. Now, intrinsic motivators can often be more powerful. (We’ve already done a full breakdown of the top intrinsic motivations.) But, we’ll quickly talk about the different types of rewards and how they function in gamification.

Types of Rewards in Gamification

When you think about the rewards in gamification that might create a behaviour change, you probably think of points and badges right away. They are the mainstays of gamification and have a lot of uses. You can get awarded for multiple logins, the first time you complete an activity, daily activity, reaching a milestone, finishing a level or meeting a time goal. Plus there are collaborative rewards to earn. These see you get gifts from friends, level up as a team or reach a new evolution together.

In fact, gamification goes out of its way to make sure nearly every positive action is rewarded. This is to further embed the behaviour change with what the organisation wants to incentivise. Overall, gamification creates choices and sprinkles motivation in the form of rewards to make those choices more appealing. Some common types or categories of rewards might be:

- Social rewards

- Virtual points/currencies

- Prizes

- Random awards

- Time-related rewards

- Fixed-action reward

- Skill badges

- Gifted & virtual goods

This list isn’t exhaustive, in fact, the full list of gamification tools and mechanics is staggering in its length and complexity.

How Rewards can be demotivating

Just remember that your rewards need to be compelling to the individual or team. If they aren’t, there’s a risk that they’ll actually demotivate your players. This can have the opposite effect on the behaviour change you’re looking for. In order to prevent this, make sure that:

- Rewards are long-term – If you want a short-term win, this will never translate to good habits or a transformational change at an organisation. You need a longer-term focus on what happens after the motivation.

- Rewards are desirable – If they don’t want what you’re offering, you’ll see no behaviour change. Maybe a reward is getting their picture on the wall as an employee of the month. Well, a camera-shy employee might actually avoid making the behaviour change to NOT have to get their photo taken.

- Rewards are broad – Remember that you want to reward improvements to the overall culture and results. Don’t sacrifice your teamwork for short-term sales improvements with an every-man-for-himself competition. Wells Fargo did this accidentally with a bonus for making new accounts that led to fraud. If their rewards were broader, they wouldn’t have created a negative behaviour change.

- Rewards lay a foundation – If you gamify all the elements that lead to success like communication, training, skills, teamwork and the like; then results will come. You don’t need to reward the end goal if you reward the steps it takes to get there instead.

- Rewards are fair – Accountability is the name of the game. If you make managers choose who gets rewarded, you’ll hear cries of favouritism. Our own personal biases mean we’re unlikely to give out rewards fairly and consistently. Instead, create a clear guideline for who will get the rewards and for what actions. Remember to think about ways that your requirements might disadvantage one group over another. For example, if you reward on percentage increase, your top performers will struggle to get much movement on already high numbers. This might cause them to tank figures one month to get the benefit in the next.